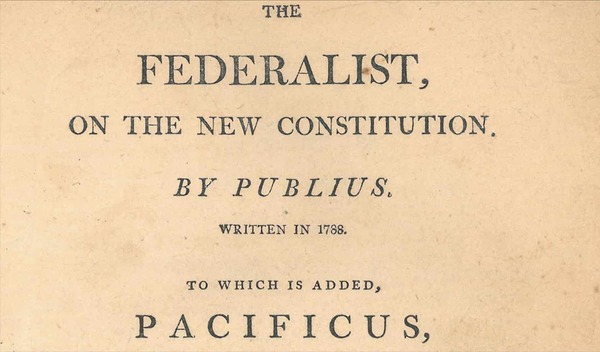

Earlier this semester, the Center for Citizenship & Constitutional Government announced the establishment of a new annual award, the Publius Prize for Undergraduate Writing on Public Affairs.

Students were encouraged to submit pieces published in the 2021-2022 academic year, so long as their article or essay fit the prize description of “refine[ing] and enlarg[ing] the public views” (The Federalist, 10). Essays were submitted by students across the campus community, covering topics as wide ranging as religious freedom, cinema and culture, and campus inclusivity. We received submissions in multiple languages and from authors of all grade levels, and are grateful to all who submitted their writing for review.

After a difficult selection process, the CCCG is proud to announce our two winners.

In the on-campus publication category, our first winner is Lizzie Self '22 for her essay "Making Universities New" published in The Rover on November 18, 2021. Her piece challenged students and faculty to think deeply about their purpose on our campus, and calls Notre Dame to consider her failings and rise to the occasion. "What," she asks "is the role of the university and its faculty if they do not take on the primary moral education of students?"

In the national publication category, our second winner is Maggie Garnett '22 for her essay "The New Yorker’s Flawed Hit Job on Amy Coney Barrett" published in National Review on February 15, 2022. Ms. Garnett's piece offers a compelling argument from the female perspective about the "feminine genius" of Justice Amy Coney Barrett. In response to Justice Barrett's critics, Maggie explores the importance of the virtues of courage, friendship, and work ethic in the world of politics.

Each author will receive a $250 prize, and their essays are copied below.

We also are proud to announce the runner up in each category, deserving honorable mention.

In the on-campus publication category, Sarah Hui's '24 piece, "Will Dining Hall Lines Ever Be Reasonable Again?", stands as an example of solid journalism. Supported by interviews with often-ignored sources on campus, Ms. Hui's piece elevates the plight of Notre Dame's staff in this time of economic hardship.

In the national publication category, we would like to commend Joe DeReuil '24 for his essay "The Kids Are Post-Liberal," published in The American Conservative. Mr. DeReuil deftly navigates the fraught political landscape among young conservatives, capturing the concerns of a generation tired of old GOP narratives without resorting to name-calling or party bashing. "The post-liberal movement is rapidly gaining popularity among university students who are witnessing the ugliest aspect of today’s liberal order," he writes. "Many who are intellectually ready to embrace this movement do not yet know what it is."

The call for next year's Publius Prize will commence in the Spring of 2023.

"Making Universities New; A Consideration of the Limitations and Ends of Higher Education" by Elizabeth Self

Something brews in Austin, Texas. On November 8, Pano Kanelos, former president of St John’s College Annapolis, announced the conception of a new university: the University of Austin. He wrote: “We are done waiting for the legacy universities to right themselves. And so we are building anew.”

Kanelos is joined by a courageous team in this project, all of whom have their own grievances with American higher education. That American universities are broken is hardly a point that needs to be sold. But how did they get here, and where is Notre Dame in the mix?

Kanelos wrote that contemporary universities have lowered their aspirations: “The reality is that many universities no longer have an incentive to create an environment where intellectual dissent is protected and fashionable opinions are scrutinized. At our most prestigious schools, the primary incentive is to function as finishing school for the national and global elite… The priority at most other institutions is simply to avoid financial collapse. They are in a desperate contest to attract a dwindling number of students, who are less and less capable of paying skyrocketing tuition.”

Notre Dame looks elite; Fr. Ted Hesburgh delivered us from irrelevance. We enjoy distinction as a “premier research university,” rankings in the top 20 in most departments, and the prestige of a $12 billion endowment. The university is able to offer more than half of students financial assistance, putting Notre Dame in the top 20th percentile of American colleges and universities for scholarships, and Notre Dame reports ranking eighth for best paid graduates. In the class of 2025, 19% are legacy students.

Notre Dame need not fear for her financial survival. But we see her behaving like other schools that do not enjoy such security, that need to clamor for attention, while she could direct her attention and resources elsewhere.

Kanelos wrote: “The warped incentives of higher education—prestige or survival—mean that an increasing proportion of tuition dollars are spent on administration rather than instruction. Universities now aim to attract and retain students through client-driven ‘student experiences’... Many universities are doing extremely well at providing students with everything they need. Everything, that is, except intellectual grit.”

As I was applying to colleges, members of admissions teams would travel to my high school and make their pitches. I understood them to be salespeople. Why did Notre Dame deserve my attention? What could I expect as a student? How would the university serve me on my path to success? Faculty are attracted in the same fashion. The employment website promises all hires to “Bring Out Your Champion!” But what is this “intellectual grit” of which Kanelos senses a lack?

Kanelos says that in failing to provide intellectual grit to their students, universities fail society, because “universities are the places where society does its thinking, where the habits and mores of our citizens are shaped. If these institutions are not open and pluralistic… if they prioritize emotional comfort over the often-uncomfortable pursuit of truth, who will be left to model the discourse necessary to sustain liberty in a self-governing society?”

This classical depiction of the university’s role in the civic sphere needs air. It serves as a reminder that we do not go to universities to be comfortable, that every body politic is inherently an aggregate, and universities ought to host a diversity of thought. Notre Dame is better and her students better formed the more she is a microcosm of the world imbued by the Catholic faith.

But something else is abundantly clear: we cannot leave the formation of young Americans’ habits and mores to universities. This task has been, and will forever be, primarily the task of the family. If students are brought up convinced that they deserve the best because they are the best, that at 18 they have already done most of the heavy-lifting they need ever do by getting into a prestigious university, if their families do not teach them how to to serve the Church and participate in diverse communities, of course they fail as students in universities. They fail in the admissions department. They fail as professors.

The Church needs parents to consider gravely their vocation as catechists and moral guides to their children. One of the principal documents of the Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, emphasizes how as the domestic church the family forms disciples: “In [the family] parents should, by their word and example, be the first preachers of the faith to their children; they should encourage them in the vocation which is proper to each of them, fostering with special care vocation to a sacred state.”

Furthermore, paragraph 2223 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church explains that homes are incubators for lifelong habits: “The home is well suited for education in the virtues. This requires an apprenticeship in self-denial, sound judgment, and self-mastery—the preconditions of all true freedom... Parents have a grave responsibility to give good example to their children.”

Families prepare youth to engage in pluralities by not abstracting them away, by not withdrawing from them in fear, but stepping into them with the hope of our Catholic faith. At universities, we do not ask students to forget where they come from and form a single hive mind. We want students who know how they are grounded and what they bring to the table. Failure in formation extends adolescence and yields further cultural confusion.

What, then, is the role of the university and its faculty if they do not take on the primary moral education of students?

The University of Austin hopes to develop a rigorous curriculum with a faculty of “society’s great doers—founders of daring ventures, dissidents who have stood up to authoritarianism, pioneers in tech, and the leading lights in engineering and the natural sciences.” Thus Kanelos essentially emphasizes that academia ought not to be isolated from “real life,” that the stigma of pretension and sloth permeating academia might be washed out of the university.

Notre Dame should proclaim that her students are already living their real lives. With their families, students first become doers, dynamic actors, disciples. At universities, they meet professors who model the many forms of discipleship, and students reflect on how they can best live a coherent life oriented toward Christ in commitment to their families, parishes, and civil communities.

At Notre Dame, our professors are the sorts of impressive people the University of Austin hopes to gather, and it is important that students learn how their work in the classroom relates to the world outside. Such transparency informs healthy student-professor relationships as well.

My favorite thing about the Program of Liberal Studies—the Great Books program of Notre Dame—continues to be how intimately we know each other, faculty and students alike. Does that make for discomfort, awkwardness, and even occasionally real pain? Of course it does. But we all generally knew what we chose when we entered the program. We wanted the real university experience, and the more it demanded of us, the better.

There remain students who want a challenge, who see Notre Dame as a place to be challenged. That is why she does not need saving, why various cultural ebbs and flows and administrative changes do not defeat her mission, why even tomorrow she can be a new university. There are many causes of the brokenness we observe in American universities, but it seems to me that a great deal of the work to be done—and the duties we often wish for universities, especially those that profess to be Catholic, to perform—starts in the home.

"The New Yorker’s Flawed Hit Job on Amy Coney Barrett" by Maggie Garnett

After reading a recent article in the New Yorker, one could not be blamed if she found herself imagining Amy Coney Barrett to be made of marble: the cold, impenetrable, masterpiece of the conservative artisan.

As a young conservative woman, I was shocked by the lengths Margaret Talbot went to caricature the newest Supreme Court justice as an almost robotic product of her male mentors and a mime for the legal philosophy that they champion, rather than an accomplished jurist exercising agency. Between sweeping generalizations about ongoing developments in jurisprudential theories, Talbot dwells — inanely and ironically — on a superficial picture of Barrett that zeroes in on her attire, “youthful-sounding voice,” and exercise habits. Talbot writes:

A fitness enthusiast seemingly blessed with superhuman energy, [Barrett] is rearing seven children with her husband…. At her confirmation hearings, she dressed with self-assurance—a fitted magenta dress; a ladylike skirted suit in unexpected shades of purple—and projected an air of decorous, almost serene diligence.

I can only imagine the outrage had this paragraph been written about another female Supreme Court trailblazer like Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Surely it would have been decried forcefully. “Not fair!” The critics would scream. “You can’t define this woman by her physical attributes! She is as hard-working, as qualified, as achieving as her male peers — and you would never speak of their attire or the frequency of their exercise.”

In this instance, I find myself in heated agreement with the critics! Yet Talbot’s efforts to discredit Justice Barrett reflect the deep-rooted so-called systemic misogyny of which conservatives are so often unfairly accused.

Talbot refuses, time and time again, to give a woman of incredible intellectual caliber — who has received perhaps the highest honor of the legal profession — any credit of her own. Instead, Talbot is almost hysterical in her efforts to tie Justice Barrett to — and define her by — her involvement with the Federalist Society, her formation under Justice Scalia, or her time at Notre Dame, which Talbot identifies as “the nation’s elite conservative law school” (emphasis in original).

Setting aside the question of whether her association with these mentors and movements is a bad thing, I am struck by Talbot’s rampant and deeply antifeminist disregard for Justice Barrett’s ability to form her own ideas. In a world that claims to celebrate women’s rights and rightly objects to the exclusion of women from fields that men have historically dominated, this is intensely ironic.

President Biden’s nominee to the Supreme Court — who he has promised will be a black woman — will be a hero to the mainstream media, in no small part because she will, if confirmed, join a small band of women who can claim that achievement. She will be presented as a self-made woman, possessing a unique voice to offer the nation’s highest court. I presume that this portrayal will be, in many ways, true. But if that female judge dares to think the wrong thing? Will she receive scrutiny of the kind Talbot has published? I predict the media will say nothing at all if they have nothing nice to say. Yet Justice Barrett is maligned time and time again simply because that same media has decided that she is the wrong kind of woman.

Women ought to make their voices heard in the public square, we are told, unless they have a conviction — about the sanctity of human life, for example — that is considered undesirable. “All are entitled to their own opinion and complete autonomy!” Progressive elites tell us, “Unless you’re pro-life, which no woman should be. If you are, you are necessarily a puppet of male interests and a traitor to your sex. You are the wrong kind of woman.”

In 2017, Senator Dianne Feinstein provided fodder for merchandise for years to come with her famous comment about “the dogma [living] loudly.” She also remarked to Amy Coney Barrett, then a judicial nominee: “You are controversial because many of us that have lived lives as women really recognize the value of finally being able to control our reproductive systems, and Roe entered into that, obviously.”

Behind Feinstein’s comment lurked the old-guard police of feminist orthodoxy. Feinstein’s “many of us” was to be perceived as “all of us.” Every woman who has really lived a woman’s life, it is insinuated, should recognize the “value of finally being able to control our reproductive systems.”

Yet, as Erika Bachiochi of the Ethics and Public Policy Center remarked poignantly in the midst of Justice Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court:

If we’re really intent as a country on seeing women flourish in their professions and serve in greater numbers of leadership positions too, it would be worthwhile to interrupt the abortion rights sloganeering for a beat and ask just how this mother of many [Justice Barrett] has achieved so much.

In some ways, Talbot cannot help but answer the question she dares not ask. She speaks of the Barretts’ incredible generosity to their children, including two adopted from Haiti and one with special needs — a generosity motivated in no small part by their deep faith. Inadvertently, Talbot highlights the unique — and thoroughly “progressive”! — balance that husband and wife found in order to allow their family to thrive. Even in this piece, Justice Barrett is a living sign of contradiction over and against pro-abortion narratives about women’s flourishing. Talbot’s interviews are testimonies to Justice Barrett’s maternal heroism and constant friendship — not because she “does it all” but because, as her husband movingly says: “You can’t outwork Amy. I’ve also learned that you can’t outfriend Amy.”

You cannot outwork Amy Coney Barrett. She is a once-in-a-generation legal mind whose scholarship, intellect, and personal care has blessed hundreds of law students for decades. She will certainly shape — and in my opinion, bless — the Court for decades to come. Why, then, does Talbot continue to insinuate that her humility must not be sincere? Why does she go to such lengths to construct a case for the Justice’s secret ambition and lifelong grooming?

You cannot outfriend Amy Coney Barrett. Colleagues and neighbors testify to Justice Barrett’s generosity and contentment with her life in South Bend: “She carefully considered opportunities as they arose, but never angled for them…. Ambition played no role in her nomination or acceptance of it. She’s not a political actor,” Justice Barrett’s colleague of twenty years (and my mother) comments.

Yet Talbot insists she knows better:

On one level, this characterization of Barrett seems genuine. She clearly had a full and busy life in South Bend, and planning to be named a Supreme Court Justice would be like planning to win the lottery. She has spoken to law students about the value of prayer when contemplating career decisions or following a calling. But downplaying her ambition — and, let’s face it, she’s gotten pretty far in life — also feeds a certain wishful narrative. It makes Barrett sound pure enough to withstand the swampy atmosphere of Washington and the careerist temptations of elite approval.

Again, ironies abound. Talbot assumes that a woman like Justice Barrett couldn’t possibly have been at peace with her vocation as a wife, mother, and professor — that she must have been scheming for more. But who is she to tell Justice Barrett what kind of woman she is, or ought to be?

I do not claim to speak for our newest justice’s jurisprudence, nor do I know how she will vote in Dobbs. Another, more legal mind should take up the questions of originalism and “common good” constitutionalism which Talbot raises in her article. I have written previously, though, about my relationship with Justice Barrett as a family friend and neighbor. For as long as I can remember, she has been a mentor and maternal figure in my life, the mother of one of my best friends, and my mother’s best friend. It is because of that relationship that I wrote this piece, and it is with that familiarity that I say only this: Amy Coney Barrett is strong enough to withstand the swamp, faithful enough to place vocation above careerist aspirations, and courageous enough to offer the world a different — truer — kind of feminine genius.